From the beginning, Eva Dixon’s relationship to making things was tied to the rhythms of labor and construction. She grew up watching their dad build the houses they lived in, convinced as a child that they were helping just as much as he was. The garage became their first studio, a place where she felt she had free range to experiment, leave tools everywhere, and sink screws and nails into whatever surfaces she could find, even if it meant putting holes in the family’s tires. Those early projects were less about producing something finished and more about absorbing the physical logic of materials, the gestures of someone solving problems with their hands. She would carry those instincts with their long after she left home, continuing to see themself moving through the world in the roles of different trades, thinking less as someone who had the luxury of an art studio and more like anyone showing up to a job where the work had to get done.

As a kid, she had already found their way into art classes at the Maitland Regional Art Gallery during school holidays. She remembers loving it immediately, especially because school itself was difficult. Art felt natural, not only because she could do it well, but because it felt expansive. Over time she realized their love of making wasn’t based on skill alone. “It was also that I found it really expansive and exciting,” she says. What she couldn’t articulate then was that the act of making gave their a freedom she struggled to feel anywhere else. As she got older she would understand this even more clearly, especially once she recognized that their ADHD made most environments feel restrictive. The studio, by contrast, became a representation of walking around inside their own thoughts. Making work was impulsive, instinctive, almost necessary. “I have a need to make things,” she says. “It doesn’t always feel like a choice.”

Those instincts followed their from Australia to England. She had finished high school without realizing art school was even an option. No one in their family had taken that path. Their dad eventually earned a master’s degree at 47, but by then she had graduated. As the eldest, she didn’t have a model for how to pursue art, yet she found herself at Central Saint Martins in London, entering a foundation year that tore down everything she thought she had learned about art-making in high school. It was disorienting. She had no idea what she was doing, but their tutors pushed their toward methods that didn’t resemble traditional painting. She began to understand there were no rules she needed to obey and that realization, she says, “radicalized me to some degree.”

University became a place where their seriousness about joy took root. She resented the idea of the tortured artist, the belief that meaningful work had to emerge from suffering. She wanted making to feel enjoyable, spirited, physical. their ideas developed through the action of making rather than sitting down and planning. When she looked back on the path that had brought their into the studio, it made sense. She had always thought through material, through tactility, through the pleasure of figuring out how something worked or why it didn’t. Working with their hands had always been the constant.

As their practice grew, she found herself in the company of people outside the art world who often engaged with their work in more surprising ways than those buying it. She remembers an older man wandering off a boat by a canal, lingering inside their exhibition far longer than collectors did. He asked their questions about hypermasculinity and meaning, ideas she could not answer, but she cherished the conversation. He saw something she wouldn’t have found on their own, and moments like this reminded their how much the reception of the work shaped its final form. When she opens a show, the things she has been thinking about for years finally cohere. Before that, everything sits in a kind of limbo between intuition and form.

Their Mercury 13 project had been on their mind for years. The thirteen women who passed the same astronaut tests as NASA’s first male astronauts but were denied the opportunity to go to space had become a subject she could not let go of. Their dedication moved her. They gave up jobs, marriages, safety, and stability to pursue something NASA did not believe women needed to do. She became particularly drawn to Wally Funk, who eventually went to space in 2021 at the age of 82 after a lifetime of waiting. Funk spent their entire life watching launches on their televisions, dreaming of a place she had repeatedly been denied. Dixon didn’t typically make work with direct messages, but this time the story mattered. She wanted to bring together what she called “non-histories” and imagine them as if they had unfolded differently. In doing so, she folded herself into the narrative as well. If she had created a world in which Funk finally went to space, Dixon imagined she had become “akin to an astronaut” in the process.

Their goals remain grounded, sometimes literally. She often jokes about wanting a dog more than anything else, but their partner made their promise they wouldn’t get one until they owned a home. So every time she sells artwork, she puts the money into the dog fund. Beyond that, she hopes for institutional opportunities, projects overseas, maybe shows in the States. But their real measure of success is simple. If she is making work she is proud of, if it brings their joy, if it opens dialogue with other artists she admires, she believes she is doing what she is meant to do. “I want nothing I’ve made now to be the best work I’ve made,” she says. “I want everything to only be better.”

Their perspective on art school has shifted with time. She once thought that their work needed to be fully justified and intellectually airtight, but a tutor eventually cut through that pressure with a single comment: “Just because you’re thinking it doesn’t mean we can see it.” It was a profound moment, one that made their cry, but it clarified everything. She also realized she didn’t need to be in a constant rush. The career is long. There is time. Watching very young artists skyrocket into blue-chip galleries made their feel an urgency she later recognized as unhelpful. What matters more, she believes, are the relationships built around the work, not the speed of recognition.

Their time on the other side of the classroom made these ideas even clearer. Working as an assistant teacher for the National Saturday Club showed their the impact of making education more comfortable for young people who have complicated lives. She loved working with teenagers, especially the ones who had never met openly queer adults in positions of authority. Even small things, like hearing their speak about their partner, changed the room. It mattered to students to see someone like them not only present but succeeding. She understood the privilege of contributing to someone’s education and of encouraging them toward something they didn’t feel brave enough to pursue. In their own teaching, she focuses less on telling students what to make and more on nurturing the confidence that allows them to make anything at all.

The art world itself can feel “Victorian,” as she puts it, archaic and strange in its social rules. She inserts herself into rooms, goes to multiple openings a week, hands out business cards. She has encountered strange comments, including suggestions that she pretend to be a man online so people would take their more seriously due to the physicality of their work. Being a woman in any space is difficult, she says, but she also found a queer community through a group show that gave their a sense of belonging she hadn’t expected. The difficulties and the joys exist simultaneously.

Their studio practice is fueled by materials that seem to find their as much as she finds them. Family members bring their objects, like the timber spools their grandmother saved after reading their book cover to cover. She still collects things from around their hometown, from op shops, charity shops, and eBay. The ratchet straps she uses often come from sellers who deal in discarded equipment no longer safe for labor. She collects postcards, fishing lures, metal tape, pieces from old sails, carpet tacks, and cloth-backed maps she bought in foundation year simply because she found them beautiful. She thinks about the labor behind them, the person laying map sheets on a table and carefully backing them with linen bit by bit. She likes materials that have been touched by work.

Their fascination with trades shows up everywhere. She watches construction workers and sees something in their gestures that mirrors their own. She loves scaffolding for its temporary nature, its ability to appear and disappear, its suggestion that something is in flux. She treats it as an exhibition structure, hanging work in space rather than on walls, embracing its impermanent logic. Even when she uses it incorrectly, tying pieces together with ratchet straps or clamps, there is joy in the directness of making something quickly and imperfectly.

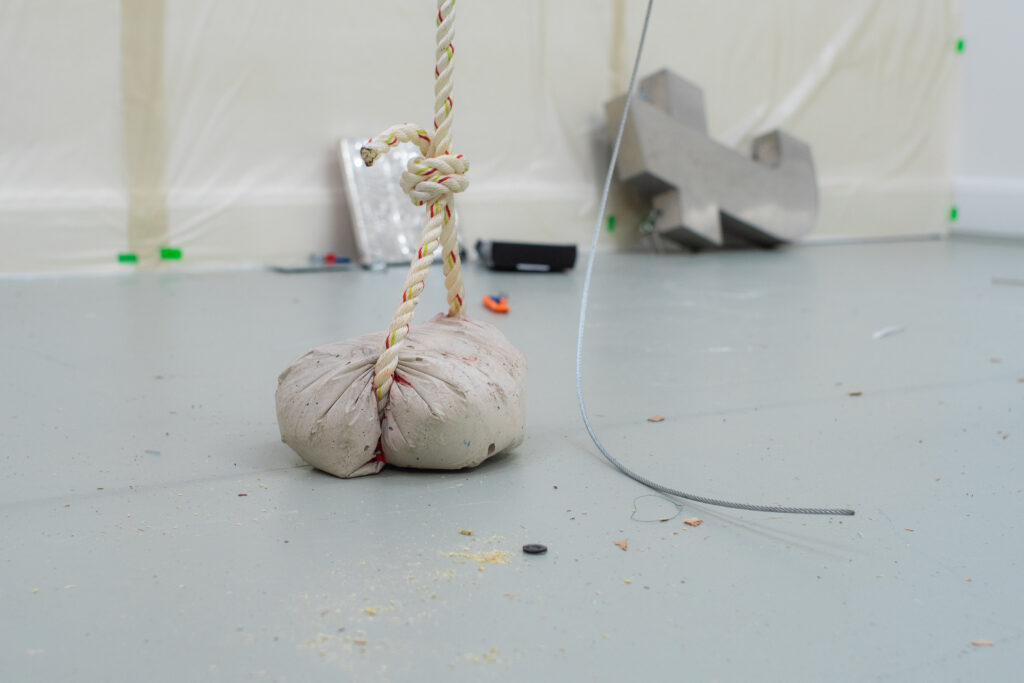

Their methods continue to echo the garage she played in as a child. She builds frames that warp, reassembles them into new forms, uses leftover materials, cuts plexiglass knowing it will chip, forces components together until they hold. She collects hardware from old stores, lifts materials out of bins, calls up local businesses to ask for discarded parts. She has used everything from fire hoses given to their by the Islington Fire Department after a surprise tour, to cables pulled from their childhood computer, to concrete cast in shopping bags, to G clamps she buys in bulk. If there is a way to do something immediate, intuitive, and technically incorrect, she will. “If there’s a way to do something that’s somewhat instantaneous and incorrect, I will do it,” she says.

Their work continues to circle back to the thrill of not understanding. She keeps pieces for years because she hasn’t solved them yet. When she begins to understand what she is making, she loses interest. Mystery, experimentation, and the willingness to fail remain the central forces in their practice. In every stage of their life, from the garage floor of their childhood to the scaffolding of their latest exhibition, she keeps returning to the same impulse: to make, to handle, to experiment, to let the work teach their something she didn’t know before. The possibility embedded in material keeps their moving forward, always looking for the next thing she doesn’t yet understand.

Hill Spriggins

Originally from New Orleans, Louisiana, Hill Spriggins has been living and working in Brooklyn, New…

Julie Stoppel

Julie Stoppel never planned to become an art teacher, or a gallery owner for that…

Nancy Goldring

Nancy Goldring remembers her first studio vividly. It was not a grand loft in New…

Yael Dresdner

Yael Dresdner speaks with the same focus that appears in her work. When she describes…

Ari Brochin

We recently had the opportunity to sit down with Ari Brochin, a multifaceted artist whose…

Antwan Horfee

Antwan Horfee’s story begins in the northern suburbs of Paris, where restlessness pushed him away…