Marc Sparfel’s story begins with an act of discovery, the kind that happens quietly, without expectation. Born in Brittany, France, he grew up surrounded by nature, with animals and trees forming the backdrop of his earliest memories. He speaks of this time as one filled with observation, a sensitivity to the natural world that would later emerge in his sculpture. It was not a childhood marked by formal art education or the idea of becoming an artist, but by an intuitive fascination with form, balance, and the quiet dignity of living things. Originally going to business school for a short period.

His first connection to making came through a kind of play. He describes collecting and building with small found objects, often discarded or overlooked things. The impulse to assemble, to give new life to what had been forgotten, was already there. But it would take years before he recognized that this instinct could become an artistic language of its own.

Sparfel’s path to art was not immediate. He moved through school without any clear sense that sculpture would define his future. Yet there was always the draw toward working with his hands. When he arrived in Barcelona, it was not with a plan to reinvent himself as a sculptor but rather to experience something different, to step into another rhythm of life. What he found there changed everything.

Barcelona, with its mixture of history and decay, its architectural layers and Mediterranean light, became the catalyst for his practice. “When I arrived in Barcelona,” he said, “I was very impressed by all the wooden furniture left in the street.” He described walking through neighborhoods where entire pieces of the city’s domestic life had been abandoned — chairs, drawers, bed frames, fragments of once-beloved objects now left behind. “At first, I took the wood to make furniture for myself,” he recalled. “And after some time, I started to make sculpture with it.”

That transition was gradual, almost accidental. There was no grand statement or formal decision. The material led him there. He began to notice how the fragments of furniture carried a kind of memory. The wood bore the marks of use, of human touch, of time passing. “For me,” he said, “it was interesting because it already had a life before.” The idea of transforming something that had lived in another form into something new became central to his process. “I started to see it like bones,” he explained, “like something that was alive before and now could live again in a new way.”

The comparison to bones is more than metaphorical. His sculptures often carry an organic rhythm, a skeletal grace. The shapes he builds evoke animals, trees, and structures that seem caught between the natural and the constructed. “When I make sculpture,” he said, “I think of animals, of their movement, of the balance they have.” The forms are rarely direct representations. Instead, they suggest motion and character — the curve of a neck, the stance of a bird, the silent watchfulness of a creature emerging from wood.

Over time, Sparfel’s process became a kind of conversation with material. He does not impose a design from the beginning. “I don’t draw before,” he said. “I just start with one piece of wood and then I add, and I look, and I listen to the sculpture.” That language — to listen to the sculpture — is something that repeats in his description of making. The act of creation is not a technical procedure for him but a dialogue. “Sometimes the sculpture tells me what it wants,” he said, “and sometimes I have to insist a little.”

This relationship between intuition and persistence defines much of Sparfel’s work. He speaks with affection about the time it takes to find the right connection, the right balance. “It’s like a dance,” he said. “You try, you move, you take one piece and put it another way, and then you feel when it’s right.” The sense of touch and the physicality of building are essential to his practice. He cuts, sands, and assembles each fragment by hand, allowing the imperfections and textures of the wood to remain visible.

In those early years in Barcelona, he worked from a small studio, often collecting his materials directly from the street. “It was a kind of ritual,” he said. “Every day I walked through the city and found new pieces. Sometimes it was good wood, sometimes not, but it was always interesting.” The act of searching became part of the creative process. Each object carried traces of its former life — a carved leg, a chipped corner, a forgotten pattern — and he learned to see potential in their scars.

Gradually, these assemblages evolved into sculptures that balanced abstraction with suggestion. Some resembled totemic animals, others were more architectural, but all retained a feeling of movement. “For me,” Sparfel explained, “it’s about equilibrium — not only physical balance, but inner balance.” He often describes the satisfaction of finding that point where everything stands on its own, where a piece that seems fragile or improbable suddenly becomes steady.

As his work developed, he began to attract attention from local galleries. The first exhibitions were modest, but they marked an important moment. “It was strange to see people looking at my work,” he said. “Because for a long time, I worked just for myself. But then I understood that when someone looks at it, the sculpture continues to live.” The relationship between viewer and object became another layer in his thinking. He noticed that people often saw animals or spirits in his forms, readings that he neither confirmed nor denied. “I like when people imagine,” he said. “It’s not necessary that they see the same as me. What is important is that they feel something alive.”

Sparfel’s process remains rooted in patience and improvisation. He speaks of his studio as a place of quiet focus, where each sculpture evolves slowly, piece by piece. “It takes time to make one sculpture,” he said. “Sometimes I start one and finish it one year later because I need to wait to understand what it wants to be.” That waiting, that respect for the rhythm of creation, defines his approach. He resists the idea of forcing a result or working toward a predetermined outcome. Instead, he allows the sculpture to reveal itself through the process of making.

Though his material remains primarily reclaimed wood, Sparfel’s relationship to it has deepened. He describes the act of giving new life to discarded things as both poetic and ethical. “There is something beautiful about using what already exists,” he said. “You don’t destroy to make something new; you transform.” That transformation carries a sense of continuity — an idea that nothing is truly lost, only changed. In this sense, his work is as much about renewal as it is about form.

Over the years, the animals that populate his sculptures have become more symbolic, more distilled. The gestures are simplified, the lines cleaner, but the spirit remains. “It’s not about representing an animal,” he said, “it’s about the feeling of the animal — its presence, its way of being in the world.” His fascination with balance extends to the emotional space of his work. “I think a sculpture should be quiet,” he said. “Not loud or aggressive, but something you can stay with, something that breathes.”

When asked what continues to inspire him, Sparfel returns to the idea of movement — the way a creature shifts its weight, the rhythm of walking, the sense of transition. He also speaks about music, about how harmony and tension in sound relate to the construction of form. “There is always music when I work,” he said. “Sometimes it helps me find the balance between pieces, like in a composition.”

His sculptures, though rooted in wood, feel surprisingly light. They occupy space with a kind of still motion, a pause caught between steps. That paradox — of solidity and movement, of permanence and fragility — is central to Sparfel’s practice. He describes it simply: “When it stands, when it breathes, it’s finished.”

Now based in Barcelona, he continues to work from his studio surrounded by fragments of wood waiting to be reborn. The space is both workshop and laboratory, filled with potential forms. He works slowly, sometimes simultaneously on several pieces, moving between them as each finds its way. “Every sculpture is a new beginning,” he said. “I never know exactly where it will go, and that’s what I like. Because if you already know the result, there is no life.”

Sparfel’s work has traveled far beyond the streets where it began. His sculptures have been shown in galleries and fairs across Europe, yet he remains grounded in the same approach that defined his early days — attentive, intuitive, guided by material and memory. The discarded furniture that once built homes now stands as part of another kind of structure, one that carries history into new form.

Looking back, he speaks with quiet gratitude. “It was a long road,” he said. “I didn’t plan to be an artist, but maybe it was always there. You just have to follow what you feel, and then one day you see that it was the right way.” For Marc Sparfel, sculpture is not about perfection or control, but about listening — to the wood, to the balance, to the quiet persistence of life itself.

Help support Timestamp (we’re an Amazon Associate) when you buy art supplies with our affiliate links (we earn a small commission at no extra cost to you):

Shop for Woodworking tools: https://amzn.to/4oiQt61

Shop for Wood Carving tools: https://amzn.to/47yWvIE

Shop for Paint: https://amzn.to/4nG9q1I

Shop for Brushes: https://amzn.to/4nJQJdQ

Kara Su

Born and raised in Berlin with Kurdish roots, Kara Su grew up far from the…

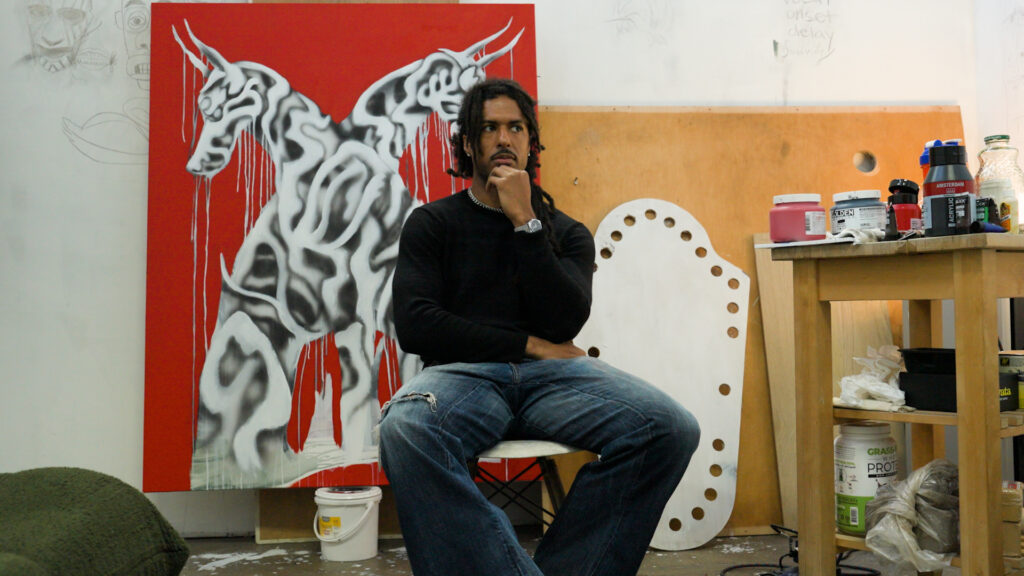

Logan Sylve

For Logan Sylve, painting is a steadfast companion. “I feel like painting is my first…

Mario Picardo

Mario Picardo approaches painting as a space of personal freedom. The studio is not a…

Hill Spriggins

Originally from New Orleans, Louisiana, Hill Spriggins has been living and working in Brooklyn, New…

Brenda Zlamany

Brenda Zlamany has been painting for most of her life, and she speaks about it…

2026 Trends in Contemporary Art: What Artists, Curators & Collectors Are Talking About

Contemporary art in 2026 is evolving at an unprecedented pace. As the art world continues…