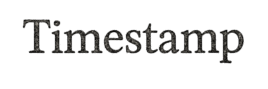

Aiden Lapp grew up in Los Angeles, performing Shakespeare from a young age and spending his early years on stage. “Kind of pretentious,” he jokes, but even then he understood that what drew him in was the chance to be with people, to study them, to shape something creative in their company. That early love for performance eventually led him toward a different stage, a quieter one. Moving to Brooklyn and studying painting, he found that the same curiosity about people could be carried forward through portraiture. Instead of learning lines and sharing them aloud, he could sit across from someone, watch them closely, and translate what he saw into marks on paper.

He describes the shift as a “pretty straightforward line of transition,” because people have always been the through-line in his work. Portraits became a way to keep asking the same questions about identity and change, only through a visual language. He is especially interested in painting his peers, people in their early twenties whose faces, styles, and even sense of self are in flux. “Capturing this moment and knowing that it’s going to be gone, and then getting to recapture it a couple years later,” he says, is what keeps him returning to portraiture. Each work is less about a finished product and more about honoring a fleeting stage in someone’s life.

For him, one piece in particular stands out. He remembers painting an ex-boyfriend and creating a watercolor that felt truer than anything he had done before. “That was the first time I was like, ‘Okay, well, I got this person on paper.’” It was a slow, careful process, but it left him chasing that same clarity again and again. He dates his first true fine art piece to around nineteen, when he felt ready to stand by what he was making. Since then, the work has been a steady practice in looking closely, sitting with people, and building a career out of those conversations.

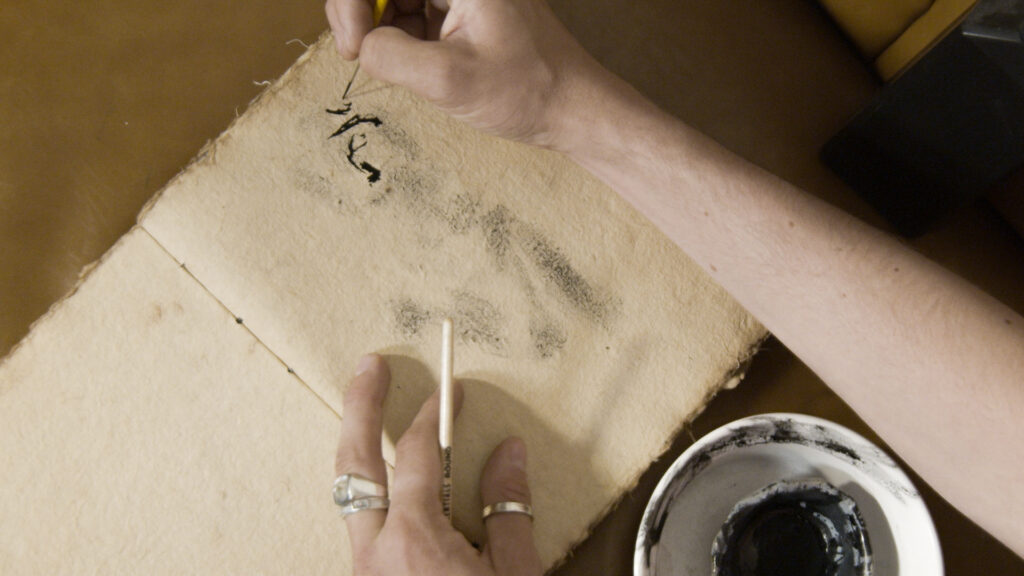

That process begins with drawing. Lapp usually starts with what he calls a “sacrificial drawing”—a thirty-minute rough sketch done just to learn a sitter’s face. Sometimes it ends up stronger than the final piece, but it always provides a foundation. The second stage is a longer sitting of two to four hours, where the architecture of the portrait comes together. He resists thinking of drawings as merely preparatory for painting. Instead, they are living documents of the shared time he has with a sitter, moments of immediacy and intimacy that he tries to preserve even after adding paint.

Drawing, he says, comes closest to the act of seeing. With color, he feels weighed down by choices, but with pencil, the gestures stay quick and responsive. He often keeps elements of that first drawing visible under layers of paint, allowing the viewer to sense both the raw sketch and the finished portrait at once. To avoid over-dependence on photos, he likes working from Polaroids, which keep him focused on the painting itself rather than the camera’s precision. A Polaroid, with its lack of detail, demands interpretation.

This approach can be seen in works like his portrait of a friend named Eddie, where the original pencil marks remain visible beneath the paint. The drawing’s immediacy lingers in the final piece, reminding both artist and viewer of the moment they first sat together. “There are so many gestures in drawing that you can’t get with painting,” he says, and yet the two enrich each other when layered. He does not see himself as strictly a painter or a draftsman, but as someone who moves fluidly between the two.

Lapp is also clear that his work is about people he loves and finds interesting. He imagines a retrospective in twenty years, showing portraits made now alongside those made in the future. What excites him is not just how his style will evolve, but how the people themselves will have changed. Hairstyles, clothes, posters on the wall—all these small details of contemporary life will eventually mark his portraits as documents of their time. “I really see this as the capturing of who people are in this moment and also who we are as a youth right now,” he explains.

Advice he carries with him comes from a residency at Oxbow, where a visiting artist told him simply: “Just make what you like.” It was a reminder that after years of art school questions about identity and meaning, the core challenge is to keep producing work despite the distractions of early adulthood. For Lapp, that means painting and drawing when he’s not working long shifts, letting his practice remain natural and close to what he enjoys most.

Influences like the School of London painters guide his approach to restraint, encouraging him to focus on subtle skin tones and the way light emerges from the paper itself. His background in watercolor has shaped the way he thinks about light and surface, often relying on the texture of cotton rag paper to do part of the work. Paper, he insists, is underestimated: durable, versatile, and far more manageable than stacks of heavy canvases. His advocacy for paper is tied to the freedom it gives him—space to experiment, to make hundreds of drawings, and to keep his process flexible.

Though painting can be solitary, Lapp values the time spent with sitters as much as the hours spent alone in the studio. Sitting for a portrait is not natural, he notes, and part of the experience comes from the awareness both artist and sitter share as they watch each other. He enjoys the small moments of recognition that happen, like when he notices a feature for the first time or when the sitter feels his gaze land on some detail of their face. His interactions are folded into the work itself, making the portrait as much about connection as representation.

His portraits are not exact copies, filtered through his own way of drawing, shaped by years of self-portraiture that has left traces of his own facial structure in the faces of others. Some sitters point out that his figures tend to have long noses or elongated features, but for him that is not a flaw. It is simply the way he sees, and with time he has learned to embrace it.

What he wants most is to continue. He has gone through stretches without a studio, filling the time with drawings he later colors once he finds a space to work. Ideally, he would like the sittings and the paintings to happen closer together, to keep the energy of the initial drawing alive in the painted surface. For now, he trusts the process he has built and focuses on doing more of it. Painting, he says, is what he is doing now, and he hopes to still be doing it seventy years from now. But more than that, he hopes to keep living an interesting life, full of good conversations, creativity, and people worth painting.

Read more: Aidan LappKara Su

Born and raised in Berlin with Kurdish roots, Kara Su grew up far from the…

Logan Sylve

For Logan Sylve, painting is a steadfast companion. “I feel like painting is my first…

Mario Picardo

Mario Picardo approaches painting as a space of personal freedom. The studio is not a…

Hill Spriggins

Originally from New Orleans, Louisiana, Hill Spriggins has been living and working in Brooklyn, New…

Brenda Zlamany

Brenda Zlamany has been painting for most of her life, and she speaks about it…

2026 Trends in Contemporary Art: What Artists, Curators & Collectors Are Talking About

Contemporary art in 2026 is evolving at an unprecedented pace. As the art world continues…