Christopher Schade speaks about painting with the conviction of someone who has been doing it for as long as he can remember. He describes his career as an ongoing loop between painting and teaching. What he makes in the studio influences what he shares with students, and what he learns in the classroom returns to his work on canvas. It’s a rhythm that has kept him committed to both for more than twenty years.

Schade grew up between Austin, Texas and Chile, surrounded by a household of teachers, writers, and academics. His father was a professor of Latin American literature, and his mother, had a deep love for visual art. “I remember going to the Prado when I was around ten or eleven,” he recalls. “When I was about twelve I had that moment, standing in front of Goya’s black paintings, and I thought: this is it. This is what I want to do.” That moment set the course. He recalls covering every scrap of paper as a child until his mother bought him a chalkboard, to keep up with his constant drawing. By twelve, painting had entered his life, and it never left.

For Schade, making art was never a choice. “It was just like a need, a drive that was so strong,” he says. Encouragement came, teachers and peers recognized his ability, and he became the kid in school who always drew, but the pull came from within. Now in his fifties, he still feels the same urgency. “When I don’t make things for a while, it starts to really affect me. It almost feels physical.”

Teaching has become as central to him as painting. Since graduate school in 1998, he has been in the classroom, now at the University of Massachusetts, Boston. The two practices feed each other. “What I make in the studio goes into the classroom and vice versa,” he says. “I learn from students, from the act of teaching, and that loops back into my work.”

The way Schade describes art-making is less about chasing a finished idea and more about dwelling in uncertainty. “If I understand the end point, I kind of don’t want to do it,” he explains. “I want it to be open-ended. I want to go into things that are fascinating but mysterious, things I don’t fully understand yet. As soon as I feel like I get it, that’s when I need to move on.”

This attraction to mystery is rooted in his background as much as his temperament. Growing up between two cultures, two languages, two landscapes, he developed a sense early on that there isn’t just one way of living or seeing. “If there are two, there must be many more,” he says. That plurality shaped his way of thinking, as did language itself. His father worked as a translator, and Schade and his brother developed a playful third language of their own, mixing English, Spanish, and invented words. “It was this really wonderful way of communicating,” he remembers, a practice that still echoes in the layered, multilingual qualities of his paintings.

Schade doesn’t want his work to hand over easy answers. He prefers questions that remain open, layered, and alive. “I try to make my paintings as clear as possible, but I also want them to have a real complexity,” he says. “I don’t want them to be confusing or frustrating, but I want people to stay with them for a long time.” He compares the experience to his own response to art that matters most to him: not solving a puzzle, but living inside it.

His influences and inspirations come from everywhere—visiting friends’ studios, looking at unfinished works, seeing how other artists set up their spaces. He and his wife, also an artist, visit museums together to recharge. “We were at the Rijksmuseum, looking at ancient Egyptian objects,” he recalls. “Just to see some of the most beautiful things humans have ever made—that’s hard to beat.”

When he advises his students, his guidance is practical and generous. He tells them to claim a space, no matter how small, and call it their studio. Reminding them to build a community around their work, the way he and friends once did by organizing a lecture series in Brooklyn. He urges them to never stop making. And he shares advice passed down from his wife: don’t be afraid to make the embarrassing work. “We all make stuff that we think is ridiculous,” he says, laughing, “but sometimes that’s exactly what leads you to something great.”

Through all of it—the childhood chalkboard, the Prado at twelve, the long hours in the studio and the classroom—what endures is the same desire that first drew him in. To make work that is clear, yet open. Posing questions without rushing to answer them. To create paintings that people want to stay with, even when they cannot be fully figured out. That is what keeps him making, teaching, and looking, all these years later.

Kara Su

Born and raised in Berlin with Kurdish roots, Kara Su grew up far from the…

Logan Sylve

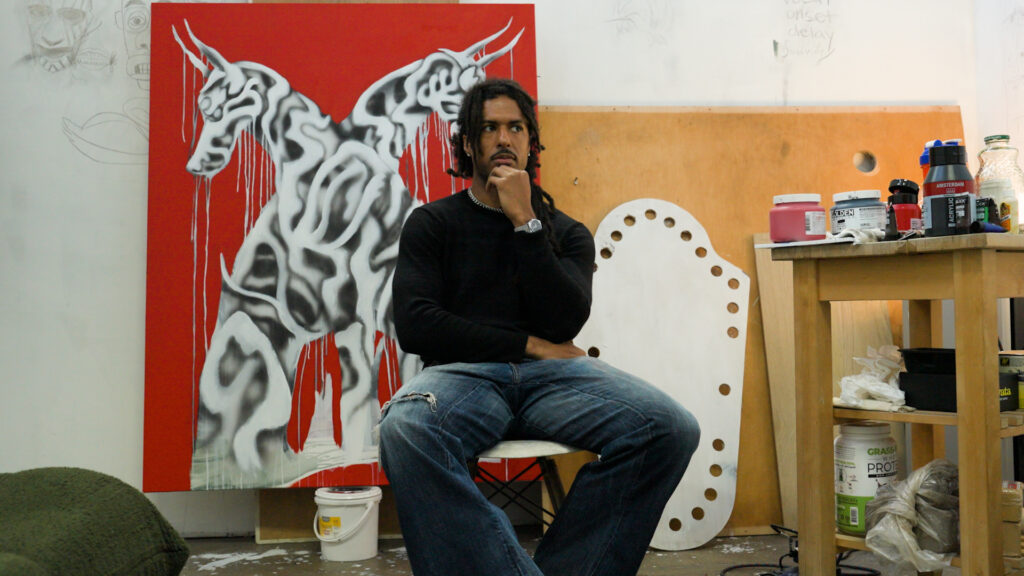

For Logan Sylve, painting is a steadfast companion. “I feel like painting is my first…

Mario Picardo

Mario Picardo approaches painting as a space of personal freedom. The studio is not a…

Hill Spriggins

Originally from New Orleans, Louisiana, Hill Spriggins has been living and working in Brooklyn, New…

Brenda Zlamany

Brenda Zlamany has been painting for most of her life, and she speaks about it…

2026 Trends in Contemporary Art: What Artists, Curators & Collectors Are Talking About

Contemporary art in 2026 is evolving at an unprecedented pace. As the art world continues…