Lydia Nobles has always needed to make art. Growing up in Bangor, Maine, she was creating from an early age. But it wasn’t until college that she realized art could be conceptual, something that could carry stories and experiences beyond representation. “I started working with my body and doing a lot of photography, video, like interacting with myself. I feel like anyone who’s engaging with the body, that’s kind of like a great starting point—working with yourself and the camera and just figuring out what you want to say and why you want to say it.”

That way of working set the foundation for everything that came later. For Lydia Nobles, art is not optional. It’s the way she processes the world. “If I’m not making art, I start to kind of get irritable and I don’t feel happy or successful. I just feel like there’s something missing. Even though I have a very full life— I feel like when I’m in the studio, I can really think through a lot of things that I just can’t do any other way.”

Nobles most recognized series, ‘As I Sit Waiting‘, started from a deeply personal place. In 2018, Lydia had an abortion. She remembers the waiting room vividly. “They were playing like Say Yes to the Dress on the TV, which felt like just not the right TV show for the moment. And then it was New York, so like people are friendly, but they’re really only friendly when they talk to you. No one was talking. And I just was so curious, like I really wanted to know what the other people in the waiting room were feeling and what they were thinking and more about their story.”

That moment of curiosity and observation didn’t leave her. When she went home she felt it was unfinished. “I felt like it wasn’t concluded and so I needed to make a sculpture about it. That would be this one back here. It’s called… originally it was called Sonogram.”

‘Sonogram’

To Lydia, the objects were as important as the memory. “This is actually like a Planned Parenthood chair and I went around and asked different Planned Parenthoods if they had like an extra chair that they wanted to throw out. So this kind of started the series.”

The work was tied directly to her memory of the procedure. “There’s a moment in the waiting room where they bring you into another room and they give you a sonogram and then they ask you if you want to look at it or not. I chose to look at it and like I still have it and I love it, but some people don’t want to look at it ‘cause it would be too hard for them. And it’s whatever makes sense for you.”

From the beginning, she wanted the series to grow beyond her own story. “I felt like because I’m in New York, I have access. A level of privilege. I wanted to hear stories from across the states. And I also knew that there were very large discrepancies between different states and what access looks like—between class, culture, all those different things that go into your identity. And I just wanted to create kind of like a waiting room experience where you could engage with those stories.”

Her sculptures often begin with discarded or found furniture. “I love to use old furniture that I find. Sometimes I’ll find like high chairs—like this one’s a high chair. Or sometimes I’ll build them independently. This one is like a rocker that I found in the trash and I just thought it was so interesting, like the movement that it allows the sculpture to have. It’s still in progress, but I’m also playing around with the paint texture and like thinking about different mattes and glosses.”

The furniture gives the work a sense of everyday familiarity, while the sculptural forms transform it into something new. The act of repurposing also reflects the emotional work at the center of the series—turning something lived into something shared.

Between 2021 and 2022, Lydia made eighteen sculptures for the series. “It was about one sculpture every three weeks. I tend to work on them all at the same time, so it wasn’t like boom boom boom, but more like a collaborative process between five or six at a time. During that time I was really able to push material and think about how shape and color interacted with each other.”

This gave her little time to experiment. Now she’s slowing down. “What I’m doing right now is thinking about ways to think about material and add more detail, crevices, more interchanging things in my work. And so my goal there is to work on that personally.”

Art is not just personal practice, it’s dialogue. “I don’t know that I have a goal professionally for the work, but what I love is when somebody kind of inspires a deeper conversation. Especially if I’m at the opening and someone is able to come and talk to me about a more intimate moment in their life that the work is bringing up for them. I love those moments.”

One memory stays with her. “In particular, there was this woman who came into a show like two years ago and she was talking about her mother. I don’t want to share exactly what she said, but I just feel like that was one of my favorite moments. I felt like, oh, I achieved something here.”

Now, she’s thinking about what comes next. “I think when you’re really young, like in college, it’s a lot of work that feels visceral because it’s connected to your experience and how you’re navigating the world. But I think that as I age, my life has become a lot less volatile. There’s not as much chaos in my life, which is great—I’m enjoying it. And I feel like right now I’m considering what does my practice look like when there aren’t moments that feel like I’m feeling a lot in my body about it. So that’s kind of what I’m balancing right now.”

Her main focus remains on reproductive access. “I interview people about their experiences with reproductive access. Through that experience, I capture different parts of their story that I want to embed in the work. And then also I incorporate broader themes related to the gesture of sitting, waiting, the anxiety involved, and different systemic ways that the government and institutions implement control over how you think about your body and how you’re able to engage with the resources that you need for your body.”

For Lydia, the work begins with lived experience and expands outward, building a collective space for dialogue. Her sculptures carry both personal and shared weight. They hold the waiting, the anxiety, and the quiet courage of choice. And they remind us that art can be a space to share what often goes unsaid.

Kara Su

Born and raised in Berlin with Kurdish roots, Kara Su grew up far from the…

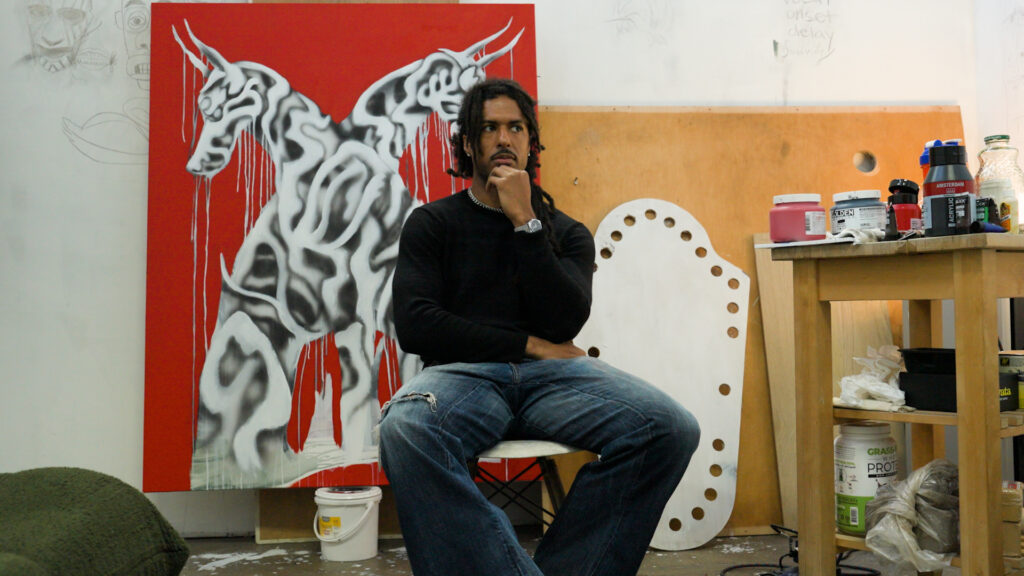

Logan Sylve

For Logan Sylve, painting is a steadfast companion. “I feel like painting is my first…

Mario Picardo

Mario Picardo approaches painting as a space of personal freedom. The studio is not a…

Hill Spriggins

Originally from New Orleans, Louisiana, Hill Spriggins has been living and working in Brooklyn, New…

Brenda Zlamany

Brenda Zlamany has been painting for most of her life, and she speaks about it…

2026 Trends in Contemporary Art: What Artists, Curators & Collectors Are Talking About

Contemporary art in 2026 is evolving at an unprecedented pace. As the art world continues…