Nancy Goldring remembers her first studio vividly. It was not a grand loft in New York or a well-lit atelier in Italy, but a corner of her family’s basement in St. Louis, Missouri. She was a child, and her mother, wanting to keep her occupied, gave her a small space to call her own. “My mother wanted to get me out of her hair,” Goldring recalls with a smile. “She set me up with a little studio in the basement with all my equipment. So I would go down there and work when I was very little.”

That small studio became the beginning of a lifelong devotion to artmaking. For Goldring, creativity was not something she learned to pursue. It was simply the way she lived. Even as a child, the act of making things with her hands felt natural and necessary. Over the years, she explored many creative paths—modern dance, music, and sculpture—but art remained her constant center. “A lot of people could do many things,” she once said. “But I don’t think I could do anything but be an artist.”

Goldring was born in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, before her family moved to St. Louis. After college, she spent several years living in Florence, Italy, an experience that would profoundly shape her understanding of beauty and form. “When I was living in Florence, I was making alabaster sculptures,” she says. “I would go to a lens factory to use their drills and stuff, and it was fun. So I never stopped.”

The light, texture, and rhythm of Italy stayed with her long after she left. When she eventually moved to New York City, the transition was difficult. “I was so miserable when I came to New York after Italy,” she says. “The first drawing I did was called Melancholia because I was just sad.” What began as melancholy soon evolved into inquiry, and her drawing practice began to take shape.

In the early 1970s, she was living in a small apartment with a view of the Empire State Building. One day, she began sketching what she saw outside her window. “I was making these crowquill pen drawings of the view outside my window,” she recalls. “Then I thought it would be really cool to see if that lined up with a photograph of it.”

At the time, she had never printed film before, but curiosity carried her forward. She learned how to develop and print her images and then photographed her drawing, combining the two large-format negatives into one. “When I sandwiched them together and printed it,” she says, “it felt like the first serious thing I’d done.” It was 1972, and that experiment became the foundation for the rest of her artistic life.

Six years later, Goldring had her first New York show. While preparing slides for a book, she made another serendipitous discovery. “I was trying to see if it was accurate enough and put it in the projector,” she remembers. “And as I turned around, it landed on the Venetian blinds. I thought, this is the coolest thing.” The light, the shadows, and the layered image created something entirely new. “I opened the blinds a little, then more, and that was my whole first show,” she says.

She had no background in photography or film. “There was no Photoshop,” she laughs. “It was all just trying to do it.” Yet through trial and intuition, she found her voice. Her work became a hybrid of drawing, photography, and projection, a language of image and light that was entirely her own.

The response was immediate. Viewers were curious, drawn to the mysterious depth of her layered images. “There was a really good response from people,” she says. “I think there was a certain amount of elation to it, but then a certain anxiety always.” Her work attracted the attention of architects, who appreciated her spatial sensibility, and soon after, she was invited to lecture at Yale. That opportunity connected her to Italian curators who had seen her show in New York and invited her to exhibit abroad. “It all just kept going,” she says. “It wasn’t so much about whether it was good or not, but about people’s curiosity.”

What struck her most was how differently audiences in Europe and America approached her work. “Here everybody wants to know how did you do it,” she says. “In Italy, they just want to talk about what they’re seeing.” The distinction mattered deeply to her. The conversations in Italy were less about process and more about meaning, perception, and experience.

By the early 1980s, Goldring’s work had expanded into large-scale installations. She created an ambitious project for a museum in Mississippi that used multiple projectors to transform an entire room. “There was nothing called installation at the time,” she says. “It’s all based on inventing a problem and solving it.” For her, experimentation was not a method but a mindset. Each piece began with a question: what happens if I try this? And sometimes, as she admits, the most surprising results came from mistakes. “Sometimes I’ll put a slide in upside down and it looks better,” she says. “You have to incorporate your mistakes too.”

Goldring continued to teach and exhibit for decades, balancing her studio practice with forty-six years in academia. Yet she never let teaching take the place of making. “You need to hibernate for a while,” she explains. “Some people just want to keep showing all the time, but I always needed time to build up and see what I was doing.”

Over the years, her process remained deeply physical. For decades, she worked entirely in analog, shooting large-format film and using slide projectors. “I used to shoot like five rolls of 36 a day,” she says. “Now it’s thirty dollars a roll, and only two places process it.” Eventually, practicality forced her to adapt. “I did a big commission in Italy and worked digitally,” she says. “It was interesting, but it’s just not the same. The film gave it a depth and made it believable, even if it was preposterous.”

Now, she finds herself in another period of transformation. “It remains to be seen if I’m going to still work with those old slide projectors,” she says. “If you can’t do that, then you have to figure out what you do want to do.” For now, that means returning to the simplicity of drawing. “Every time I sit down to do a new drawing, I think, okay, this is going to be the most beautiful drawing I’ve ever made.”

For Goldring, beauty is not a sentimental ideal. It is the essence of connection between artist and viewer. “It’s not fashionable today,” she says, “but beauty adds a lot to people’s lives. There’s no reason for it not to be beautiful. The more articulate a work is, the more you’ve given to your public.”

Her work often explores cultural perspectives on space and vision. Having traveled extensively through Asia, she became fascinated with how different traditions perceive depth and distance. “When I went to China, I tried to figure out what their perspective system was,” she recalls. “I asked an assistant from China, and they said, the vanishing point is wherever you are in the picture.” That answer, both poetic and profound, perfectly mirrored her own approach to art.

Today, Goldring’s studio remains a space of experimentation, filled with models, transparencies, drawings, and projections. She still works by layering, aligning, and photographing intricate constructions by hand, a process that can take over a year for a single piece. “It’s many possible solutions,” she says softly, “and they’re all true.”

When asked what advice she would give to young artists, her response is immediate. “Stop being miserable and get to work,” she says. “You shouldn’t regret choices you’ve made. And it should all be fun.”

After a lifetime of making, teaching, and experimenting, Nancy Goldring still approaches each project with the same sense of wonder that filled her basement studio as a child. She has built a life not just around art, but through it. “It starts with drawing,” she says. “But it’s really about how you see.”

Help support Timestamp (we’re an Amazon Associate) when you buy art supplies with our affiliate links (we earn a small commission at no extra cost to you):

Shop for Canvas: https://amzn.to/4nG9q1I

Shop for Brushes: https://amzn.to/43blY9M

Shop for Pencils: https://amzn.to/47FM06B

Shop for Projector: https://amzn.to/47QzYs6

Shop for Film Cameras: https://amzn.to/3X6aBwa

Kara Su

Born and raised in Berlin with Kurdish roots, Kara Su grew up far from the…

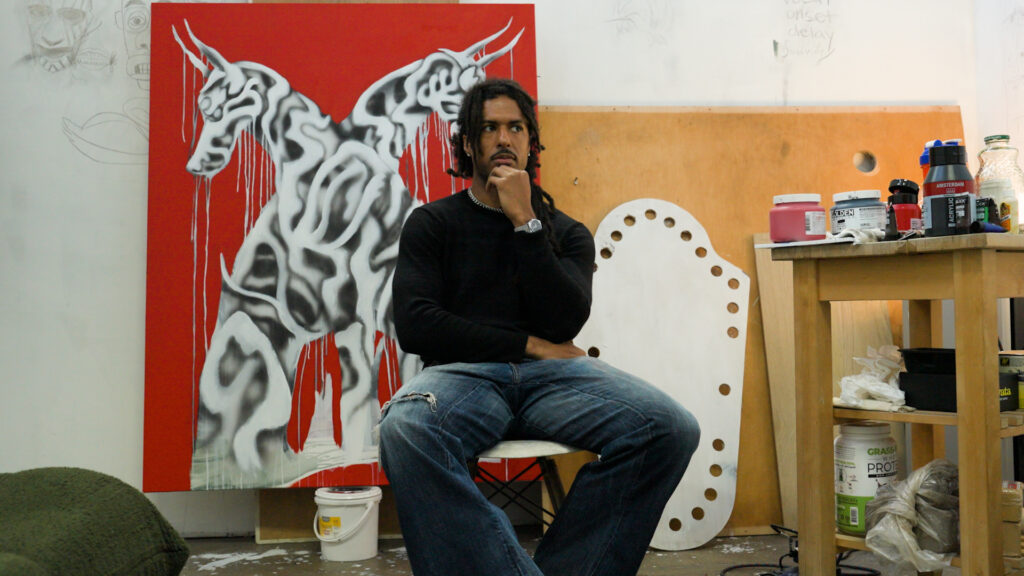

Logan Sylve

For Logan Sylve, painting is a steadfast companion. “I feel like painting is my first…

Mario Picardo

Mario Picardo approaches painting as a space of personal freedom. The studio is not a…

Hill Spriggins

Originally from New Orleans, Louisiana, Hill Spriggins has been living and working in Brooklyn, New…

Brenda Zlamany

Brenda Zlamany has been painting for most of her life, and she speaks about it…

2026 Trends in Contemporary Art: What Artists, Curators & Collectors Are Talking About

Contemporary art in 2026 is evolving at an unprecedented pace. As the art world continues…