In a quaint little town in Michigan we came across a beautiful home of bright colors and paintings hung on the exterior. As we grew closer, the mounds of oil paint tubes in the garage welcomed us in. This is the home of artist Ellie Harold.

At 52 years old, Ellie Harold picked up a paintbrush and changed the course of her life. Today, she is a professional oil painter and installation artist based in Frankfort, Michigan. Her work has been exhibited internationally, featured in U.S. embassies abroad, and collected by admirers around the world. But Harold’s journey into art was not straightforward. It was shaped by trauma, ministry, and eventually a deep calling that emerged when she least expected it.

“I began painting in 2003 in response to what I consider to be a second calling,” she explains. As a child she had been interested in art, but her father, a commercial artist, discouraged his children from pursuing it. “I grew up believing I didn’t have what they call ‘talent’. I had taken art classes at different times and basically just dropped them. In high school, I got a C on my first project and I said, ‘There goes my grade point average.’ So I dropped my art class.” The idea of being an artist faded, though she briefly attempted an oil painting class twenty years before beginning in earnest. She lasted three weeks. “I had totally given up all hope.”

What brought her back was not ambition but survival. In 2002, the Catholic church abuse scandal broke nationally. Ellie, herself a survivor, felt compelled to speak out. “I was one of those kids who got molested by a Catholic priest when I was a child. And in 2002, when the story broke nationally, I realized it was important for me to go public with my story.” She connected with the Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests. That involvement was draining. At a meeting in Boston she found herself unable to sleep. “For three nights I just lay in bed and this little voice said, ‘Do art, do art, do art.’” Ellie had once experienced a profound call to ministry, and she recognized this as a similar summons. “I realized that even if I didn’t understand what it meant, I had to explore it.”

Back home in Atlanta, she bought art supplies and set them up in a corner of her porch. “I just sat and looked at it for like six months. I had no idea, no desire. And then one day I just saw some flowers outside and I said, “I’m going to paint those, and I just never stopped.”

She was fifty-two years old. “I’m now seventy-three. I’ve made several thousand paintings. I’ve sold quite well. I have paintings in the U.S. embassy in Kyrgyzstan. Collectors have taken my work to Germany and England. I can claim a certain amount of modest international recognition.”

The recognition, however, is not what drives her. “When I started, I was just curious to know if I had that thing they call talent, because I so didn’t believe that I did.” She painted still lifes, then landscapes, before moving toward something more expressive. Around 2016, birds began appearing in her work. At first, she resisted. “I shuddered at the thought of painting birds. I didn’t want to be a Hallmark card artist.” But the birds persisted. “They came to reveal themselves to me as intuitive messengers of hope and healing for a troubled world.”

This shift coincided with a broader opening in her creative process. She began painting more intuitively, abandoning her impressionist palette and embracing black paint. “I found that my problems at the time — not being able to sleep, a lot of fear about what might happen — poured out onto the canvas. And I realized there was something greater than me actually motivating and executing my art. My worst paintings come when I have an idea. The best ones come when I surrender. All I had to do was get my fear out of the way.”

Her collaborative installation Birds Fly In: A Human Refuge grew from this discovery. Created with composer David Mendoza, it explored migration, belonging, and spiritual refuge. “It’s themed around human migration, using birds as a metaphor. Looking for spiritual solutions to problems that policies don’t seem to be able to solve.” The installation has shown in museums and galleries and remains an important part of her practice.

Harold describes her relationship with art as one of freedom. “Even when I start a painting completely randomly, just with black calligraphic marks and random colors, something beautiful and unexpected occurs that doesn’t really have to do with my intention.” Her philosophy echoes her years in ministry: “When I was a public speaker, I came to the point where I realized I didn’t really know what to say. But something higher than me did. And all I had to do was get my fear out of the way.”

She doesn’t censor herself or restrict her work to one style. “I know I can be extremely abstract, I can render things representationally. I don’t like to say, ‘This is the kind of art I make.’ I just try to stay loose with it and let it happen.” That openness conveys itself to viewers. “The indirect message of my work is freedom. We confine ourselves with beliefs about ourselves and others that keep us in a cage of limitedness. But we can be free.”

Freedom, she says, has been a lifelong pursuit. “There’s a picture of me as a little girl standing on a fence. My mother said I would just say, ‘Let me out, let me out.’ I think there’s something in my spirit that has never wanted to be confined — not by other people’s definitions of me, nor by my own self-limiting doubts and fears.”

Harold knows the cost of self-denial, especially for artists. “I’ve had people, mainly other artists, come into my studio and burst into tears. They feel the freedom here. For artists who aren’t making work, it’s painful, because I believe there’s something spiritual in nature that wants to come out. To thwart that spirit is one of the most painful experiences you can have if you’re called to be an artist.”

Ellie Harold’s journey has been one of healing, courage, and surrender. From childhood discouragement, to trauma, to an unexpected second calling, she has built a life that proves the power of creativity to liberate. “I think my thesis is freedom,” she reflects. “All I had to do was get my fear out of the way.”

Help support Timestamp (we’re an Amazon Associate) when you buy art supplies with our affiliate links (we earn a small commission at no extra cost to you):

Shop for Canvas: https://amzn.to/4nG9q1I

Shop for Paint: https://amzn.to/47UVtsh

Shop for Brushes: https://amzn.to/4nJQJdQ

Kara Su

Born and raised in Berlin with Kurdish roots, Kara Su grew up far from the…

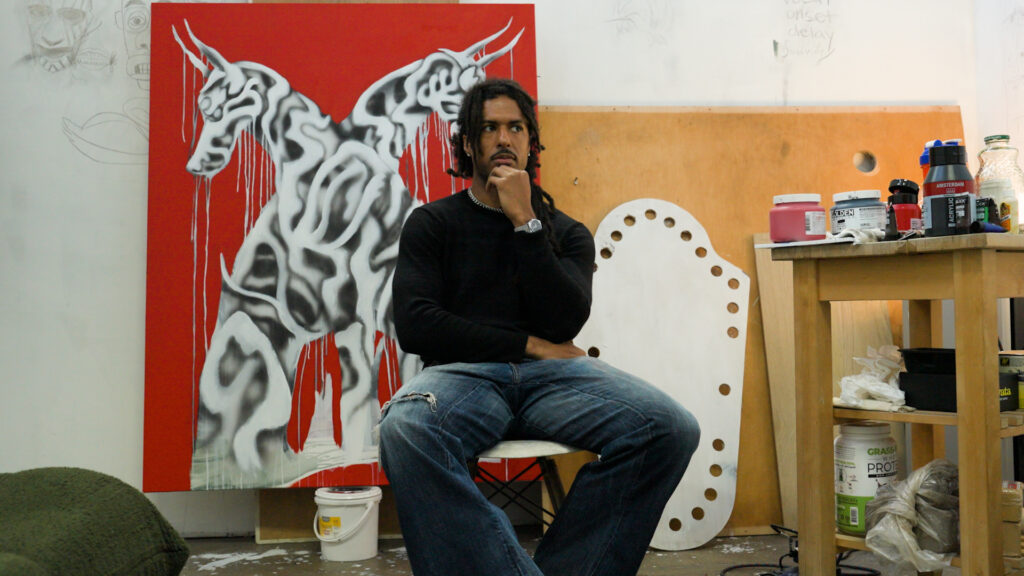

Logan Sylve

For Logan Sylve, painting is a steadfast companion. “I feel like painting is my first…

Mario Picardo

Mario Picardo approaches painting as a space of personal freedom. The studio is not a…

Hill Spriggins

Originally from New Orleans, Louisiana, Hill Spriggins has been living and working in Brooklyn, New…

Brenda Zlamany

Brenda Zlamany has been painting for most of her life, and she speaks about it…

2026 Trends in Contemporary Art: What Artists, Curators & Collectors Are Talking About

Contemporary art in 2026 is evolving at an unprecedented pace. As the art world continues…