There has never been anything Eleanor Arbor enjoys more than making. It is not about prestige or outcome, but about the act itself. She describes art not as a special talent set apart from the rest of life, but as a way certain people are wired. In her words, if you are truly an artist in your soul, you go crazy if you are not making art. She does not say this to elevate one type of person over another, but to describe a difference in temperament. Some people are athletes. Some people are academically inclined. For her, making is a necessity. When she does not make, her sense of self erodes. Her mental health declines. She becomes irritable and disconnected. Making is not optional. It is how she stays grounded in reality.

Arbor grew up in Boston, Massachusetts, and now lives and works in Los Angeles. She has no clear memory of beginning to make art, only the sense that it was always there. Like most children, she was given art materials as a standard activity, but she took to it with unusual intensity. As a mother herself now, she recognizes how common early art-making is, but also how not everyone holds onto it. For her, it never fell away.

Her first vivid artistic memory centers on clay. In middle school, her mother enrolled her in classes at a community art center because she had an abundance of energy and an obsession with art. One of those classes was wheel throwing. Arbor remembers touching clay on the wheel for the first time and feeling an immediate, physical pleasure. She describes it as one of the most pleasurable sensations she had ever experienced. Anyone who has worked with clay understands, she says, how good it feels in the hands. That moment stands out as the closest thing she has to an artistic awakening, not because it marked the beginning, but because it clarified something already present.

Clay remained central to her practice for many years. She majored in ceramics in art school and gravitated toward figurative, sculptural work. Even then, she noticed that her attention kept returning to the surface rather than the object alone. Texture, finish, and material behavior mattered deeply to her. Ceramics offered a layered experience of surface, with the clay itself and the glaze interacting on top of it. She describes it as a kind of party, an abundance of tactile information.

At the same time, she found herself drawn to flat forms. She made tablets and wall-oriented ceramic works, but large-scale clay quickly became impractical. Clay resists being flat, and working at scale is expensive and logistically difficult, especially in a city. Eventually, cost and feasibility pushed her to look for a different material that could scratch the same itch.

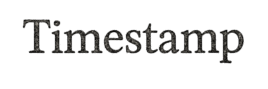

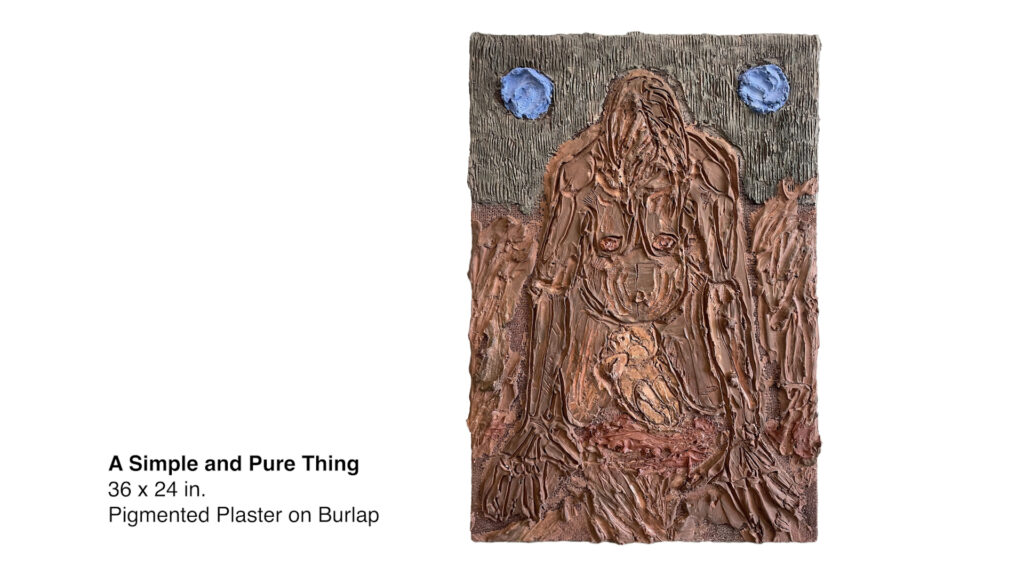

That search led her to plaster. She had encountered it before in school while making molds for ceramics and already understood how to mix it and what it could do. She began experimenting, making plaster the primary material rather than a supporting one. The shift was practical, but it was also intuitive. Plaster could behave like clay in some ways while offering different advantages. It allowed her to work larger, faster, and with less fragility. It did not require the same level of constant attention. It was inexpensive and accessible. She could buy it at a hardware store and get to work.

Over time, plaster became central to her practice. She emphasizes that nothing fully replaces clay for her, but plaster comes close. She has spent years developing her process, learning what the material can do and how to push it. The way she uses it now has been evolving for about five years, shaped through sustained experimentation rather than sudden change.

Drawing plays a significant role in that process. Arbor produces large volumes of sketches, often on simple computer paper. She draws quickly and repetitively, returning to forms she likes and riffing on them again and again. When an image holds her attention, she wants to carry it with her, tape it to the wall, move it around, and live with it physically. This practical need led her away from traditional sketchbooks, which felt restrictive. Tearing pages out disrupted their function, but keeping them bound prevented her from working the way she wanted.

Eventually, she reintroduced the idea of a sketchbook in the form of scrapbooks. Loose sheets accumulate while she is working, scattered throughout the studio. When she collects them, she often discovers repeated forms and motifs, evidence of her thinking looping back on itself. Some pages test color mixes for plaster. Others refine figures. Once she feels she has extracted everything she needs from a drawing, she places it into a scrapbook. Over time, those books become both archive and generator, a visual journal she can flip through to rediscover forgotten ideas and reenter earlier states of mind.

This cyclical relationship between making, collecting, and revisiting mirrors how Arbor describes her broader artistic life. Nothing feels linear. The work changes as she changes. Materials shift. Focus shifts. But the underlying need to make remains constant.

That need persisted even during periods when her traditional studio practice paused. Over the past year, Arbor stepped away from the studio to be a full-time stay-at-home mother with her second child. It was the longest break she has taken from her formal practice, but not from making entirely. She continued to create in different ways, adapting to the constraints of that phase of life. Still, she felt the absence. She describes losing her sense of self and feeling unmoored when she is unable to make. The impact is emotional, psychological, and physical.

Now, she is returning to her studio practice in a garage in Los Angeles, making wall-based works intended to move from studio to gallery or directly into homes. She speaks about this not as a grand return, but as a continuation. Throughout her life, making has taken different forms. Sometimes it was ceramics. Sometimes it was painting the walls of her house different colors over and over, obsessing over the details until the need was temporarily satisfied. Each form gave her a runway, a way to stay connected to herself.

Motherhood reshaped her goals, both personally and artistically. She describes a narrowing of focus that comes with parenting, not in a negative sense, but as a recalibration. Life goals become simpler and more essential. She wants a beautiful life with her family. She wants her children to be healthy and happy and to grow up in a positive environment. Being a good mother requires her to take care of herself, to stay mentally and emotionally balanced, which brings her back again to making.

Artistically, beyond the conventional markers of success like exhibitions or sales, she wants growth. She wants her work to get better. She wants it to change. She does not believe in infinite expansion, but she does believe in evolution. She wants her craft to reflect her experience and age, to avoid stagnation, and to remain dynamic.

When asked about message or meaning, Arbor resists reducing her work to a single idea. She describes it more as a series of vibes that shift from piece to piece. Visual art, she notes, does not always translate cleanly into language. If she were better at that, she jokes, she might be a writer. Still, she identifies recurring themes rooted in her own psyche and lived experience.

She speaks openly about her spirituality, her belief in God, and her connection to nature. Motherhood has deepened her awareness of the body, of birth, and of life cycles. These ideas surface in her work through imagery of plants, insects, and landscapes. She is particularly inspired by Southern California flora, by cactus blooms, agave life cycles, and the rhythms of growth and decay. Fire and regrowth, which are natural parts of the local ecosystem, also inform her thinking. She acknowledges their destructiveness while emphasizing that they existed long before humans and will continue after.

Underlying all of this is a sense of awe. Arbor says she is not jaded. She likes feeling small in a good way. She is interested in remembering that humans are part of something much larger. Being alive, she says, is the closest thing she can offer as a unifying theme for her work. The art is about being alive.

That perspective extends to how she views anxiety about the future. She reflects on how easy it is, especially when young, to worry about how life will unfold. With time, she has learned that things oscillate. Everything will be fine, then it will not be, then it will be again. Her advice is simple and hard-earned. Enjoy life as it is. Be a good person. Keep making. She did not need encouragement to continue making, but she did need permission to stop worrying about how everything would turn out. From where she stands now, she feels good about the life she has built and recognizes that it is still unfolding.

Eleanor Arbor’s practice is not defined by a single medium, message, or moment of revelation. It is defined by persistence, material curiosity, and an unwavering commitment to making as a way of staying whole. Her work grows alongside her life, shaped by motherhood, spirituality, environment, and time. Through all of it, the impulse remains the same. She makes because she must, because it is how she understands herself, and because, for her, being alive means making things.

About the Author

Sam Burke is an American artist and writer based in New York City. Working across film, performance, and writing exploring storytelling, identity, and place. As co-founder of Timestamp, Burke interviews artists, shares insights, and highlights conversations shaping art world today.

Kara Su

Born and raised in Berlin with Kurdish roots, Kara Su grew up far from the…

Logan Sylve

For Logan Sylve, painting is a steadfast companion. “I feel like painting is my first…

Mario Picardo

Mario Picardo approaches painting as a space of personal freedom. The studio is not a…

Hill Spriggins

Originally from New Orleans, Louisiana, Hill Spriggins has been living and working in Brooklyn, New…

Brenda Zlamany

Brenda Zlamany has been painting for most of her life, and she speaks about it…

2026 Trends in Contemporary Art: What Artists, Curators & Collectors Are Talking About

Contemporary art in 2026 is evolving at an unprecedented pace. As the art world continues…