Born and raised in Berlin with Kurdish roots, Kara Su grew up far from the traditional art world. Her mother raised seven children on her own. Galleries, collectors, and studio culture were not part of her environment. Art school existed in primary education, but the idea of becoming a painter did not.

In her twenties she tried other paths. Regular jobs. Practical choices. Stability. None of them felt true. The instinct persisted. The feeling that she was born a painter and only needed to remember it.

At nineteen, while living in Australia, that instinct became practical. She painted on found wooden pieces while working as a bartender and waitress. People responded. They wanted to buy the work. The equation became simple. She enjoyed painting more. The realization did not arrive as a grand artistic awakening. It arrived as clarity.

The road from that clarity to commitment was not easy. Painting requires materials, space, time, and money. For someone without financial privilege, those are not small barriers. She describes the decision to become an artist as something that must be made repeatedly. Even if it means going broke. Even if the outcome is uncertain.

Today she studies at UdK Berlin. For her, the academy represents access, studio space, conversations with professors, exposure to collectors and galleries. A network that would have been difficult to enter alone. She is clear that university is not required to become a great artist, but it can make the path more accessible.

Her goals are unapologetically ambitious. She wants major institutions, she wants to return to New York, she wants the largest studio she can imagine. “I want it all,” she says. Not as fantasy, but as direction.

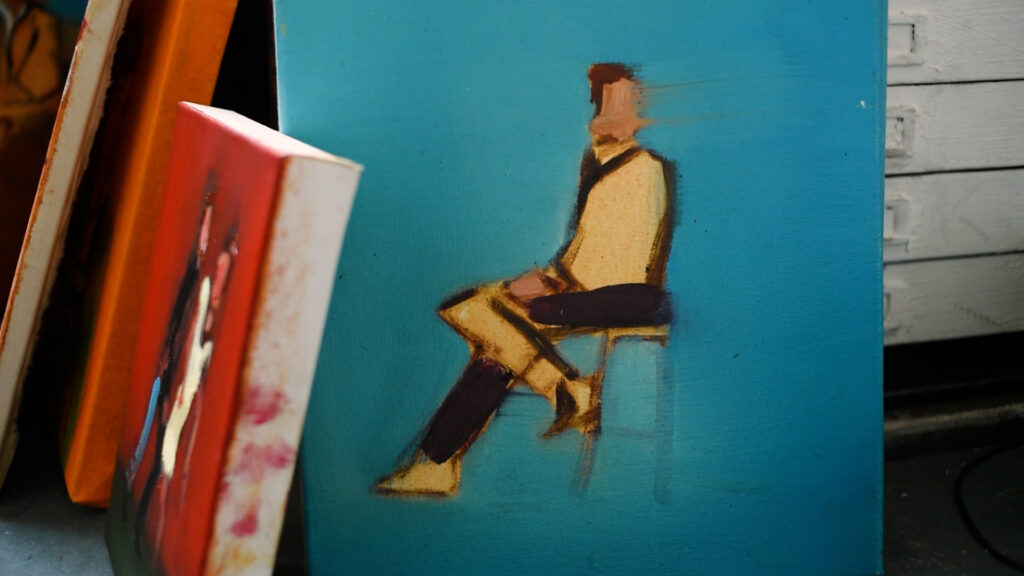

Kara Su’s work is currently figurative and psychological. She paints individuals or groups, often suspended in what she calls unfinished thoughts. The narratives remain open. Viewers are invited to complete them.

A professor once told her that her art had become an extension of her soul. She keeps the work personal but not closed. Real to her experience, yet open enough for identification. The figures often resemble her. Friends and family notice it immediately. Self portraiture became a tool for self examination, especially during her time in New York.

Before that shift, she experimented widely. She painted musicians like Jimi Hendrix. Over time, she questioned whether she was painting what felt authentic or what she thought she should represent. In New York, she turned inward. The self portraits were not vanity projects, they were investigations. Who am I beyond narrative, beyond expectation?

That series unlocked momentum. She stopped seeking permission or external validation. Earlier in her career she asked others for confirmation, for reassurance that she was on the right path. Now she trusts her intuition. If others do not understand the message, she accepts that. They do not have her imagination or her internal landscape.

She began with acrylics because they were affordable. At UdK she transitioned into oil painting. Oils offered time. The slower drying surface allowed extended movement and layering. She acknowledges the hierarchy historically attached to oil, from Renaissance masters to contemporary painters, but she is pragmatic. She does not use the most expensive materials. Medium priced oil tubes, affordable synthetic brushes, often bought in bulk.

The process begins with sketches, underpainting, a structural outline. After that, the painting becomes instinctive. She follows impulsive thoughts. Earlier she was afraid to deviate from the plan. Now she moves freely once the foundation is set.

Sometimes a canvas hangs unfinished for weeks. She observes it while working on other pieces. In her mind, the painting resolves before her hands touch it again. When she returns, execution can take thirty minutes. Other times it takes far longer. She recognizes completion intuitively. There is no formula, the painting feels finished.

She builds many of her own stretchers. In New York she learned to construct wooden frames herself from an artist who had worked closely with Robert Rauschenberg. When she returned to Berlin, she carried nearly thirty unstretched canvases home in a single rolled package, registered as sports luggage to ensure they made the flight. The physical labor around painting is part of the practice.

Scale matters, large canvases offer physical movement. Smaller works allow experimentation and speed. She moves between both, often developing ideas in small formats before translating them into larger compositions.

Life is her primary reference. Sceneries, conversations, relationships. Music plays a central role in her rhythm. She describes her painting style as influenced by jazz, improvisation, layering, harmony emerging from apparent fragmentation.

Art fuels the studio, Kendrick Lamar, Patti Smith, and David Lynch represent for her a kind of artistic integrity. Creators who commit fully to their internal vision. She references a conversation between Lynch and Smith about finding a piece of a puzzle and sensing the larger image waiting in another room. That metaphor aligns with her experience, each painting feels like a fragment of something larger she is still assembling.

Other painters enter the conversation through suggestion and comparison. Viewers mention expressionism or Francis Bacon when they see certain distortions in her figures. She does not deny influence. She believes it is natural to absorb what resonates, but copying without transformation feels empty. Influence should pass through the filter of one’s own perception.

As a woman entering the art field, she encountered attempts at exploitation. Offers framed as opportunity but rooted in imbalance. She learned to recognize and distance herself from those dynamics. Fair contracts and professional relationships exist. It requires discernment and boundaries.

Financial instability has tested her commitment more than once. After returning from New York without the breakthrough she envisioned, she felt defeated, burned out. Questioning how many attempts it would take before the door opened. The answer was consistent. When she stops painting, she feels worse. The work itself restores direction.

She describes the artistic path as swimming across an ocean while most people stand on stable ground. There are periods of sales and periods of silence. The decision to continue must be internal. Encouragement helps, but belief must originate from within.

Kara Su calls herself a chameleon. She does not intend to remain fixed in one visual language forever. For now, the figurative series centered on identity and open narratives feels authentic.

Titles often carry affirmations. She believes thoughts shape reality. Naming a painting can be a form of manifestation. A reminder that the path she envisions exists ahead of her.

Her next ambition is space, a larger studio. The ability to paint multiple large canvases simultaneously. For Kara Su, painting is not a strategy. It is not a fallback. It is not even primarily a career choice. It is the act of remembering who she is. As long as she continues to paint, the memory remains intact.

About the Author

Sam Burke is an American artist and writer based in New York City. Working across film, performance, and writing exploring storytelling, identity, and place. As co-founder of Timestamp, Burke interviews artists, shares insights, and highlights conversations shaping art world today.

Kara Su

Born and raised in Berlin with Kurdish roots, Kara Su grew up far from the…

Logan Sylve

For Logan Sylve, painting is a steadfast companion. “I feel like painting is my first…

Mario Picardo

Mario Picardo approaches painting as a space of personal freedom. The studio is not a…

Hill Spriggins

Originally from New Orleans, Louisiana, Hill Spriggins has been living and working in Brooklyn, New…

Brenda Zlamany

Brenda Zlamany has been painting for most of her life, and she speaks about it…

2026 Trends in Contemporary Art: What Artists, Curators & Collectors Are Talking About

Contemporary art in 2026 is evolving at an unprecedented pace. As the art world continues…