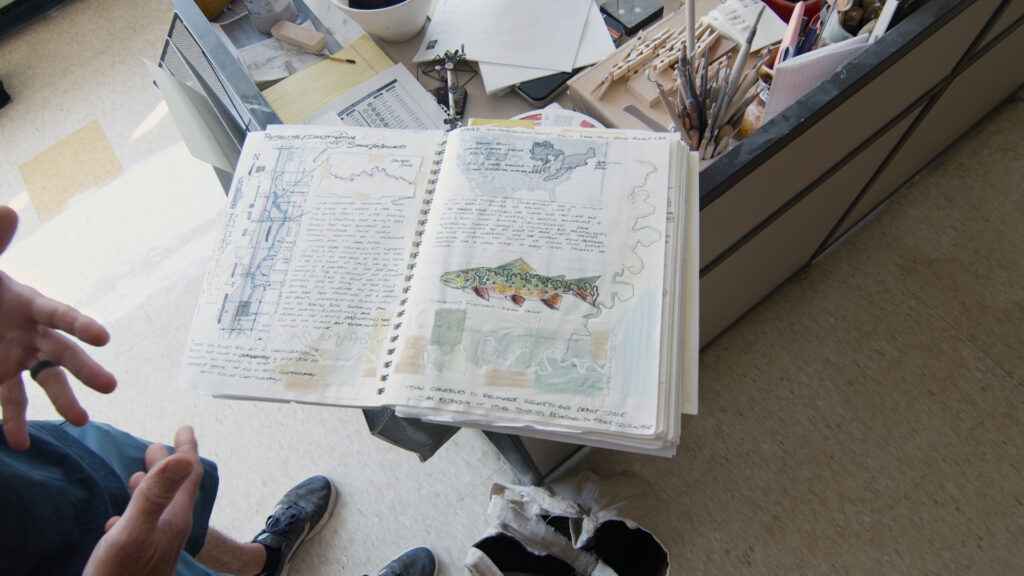

Terry Szpieg grew up in Muskegon, Michigan, and from as far back as he can remember, drawing was simply something he did. It required no special materials and no permission, only curiosity and a pencil. When he visits his parents today, his mother sometimes pulls out his old sketchbooks from elementary school, filled with birds, pieces of her garden, and early attempts at perspective. He looks at them now with a mix of nostalgia and amusement, reminders of the long arc of growth that art demands. Even the technical skills he teaches today, like perspective drawing, still feel open ended to him. He believes that no matter how skilled you become, there is always a way to push further.

That sense of endless possibility sits at the root of why art became a constant for him and why it eventually shaped his career. Although he never set out with a clear plan to become a teacher, his family history nudged him in that direction. His mother was a teacher, his sister became a teacher, and his father worked as an engineer. During his sophomore year at Western Michigan University, his advisor and oil painting instructor, Ellen Armstrong, noticed he still had not declared a major. She walked him through the realities of his life, asked questions about his family, and ultimately suggested he try education. Western had a strong program, she told him. He agreed, uncertain whether he was making a thoughtful choice or simply caught up in the momentum of school and life.

He sometimes jokes that he still wonders if he chose the right path. There are days he thinks he should have gone into engineering, or into a design field like industrial design or architecture. At fifty four, with a wife, children, and decades of teaching behind him, those questions linger in a distant and almost abstract way. His job has given his family stability. It has also placed him inside a role that feels deeply complicated.

For twenty six years at East Grand Rapids, he has been the person who introduces students to art not as a luxury but as a moment of pause in a life that often feels too fast. He sees how much pressure young people carry and how art class can briefly cut through that noise. He believes that working with a pencil or clay or a welder’s torch allows students to step away from the intensity of their daily lives. Yet he also knows that most people do not see art that way. They view it as something superficial or optional. He talks to his classes about the therapeutic qualities of creating.

Some students carry the experience with them long after graduation. Those students are what keep him returning to the classroom each day. He remains in touch with many from as far back as twenty years ago. Some have become architects, industrial designers, photographers, or creators in fields that blend art with function. One former student works as an industrial designer in Oslo, prototyping cookware. Scattered across the world, carrying forward the same sense of creative fulfillment that first took shape in his classroom.

He receives emails, letters, small gifts, and updates from former students who tell him how art helped shape their path or how something from his class resurfaced in their lives years later. These moments arrive without warning. He calls them his delayed gratification, the quiet rewards that help him endure the more difficult aspects of the job.

Teaching does not leave him much time to make his own work. He recently finished a charcoal drawing that took two years because he squeezed it in between teaching, grading, and family life. He makes a point of working alongside his students on classroom projects so they see that he can do the same work he asks of them. He pushes back gently at the idea that those who teach art do so because they cannot make it themselves. He insists the opposite is true. His limited output has nothing to do with ability and everything to do with time. Managing six class preps, raising a family, attending soccer practices and concerts, and balancing the constant demands of school take priority over his personal creative pursuits. Only other art teachers, he says, truly understand what that feels like. Many days are, in his words, a kick in the teeth.

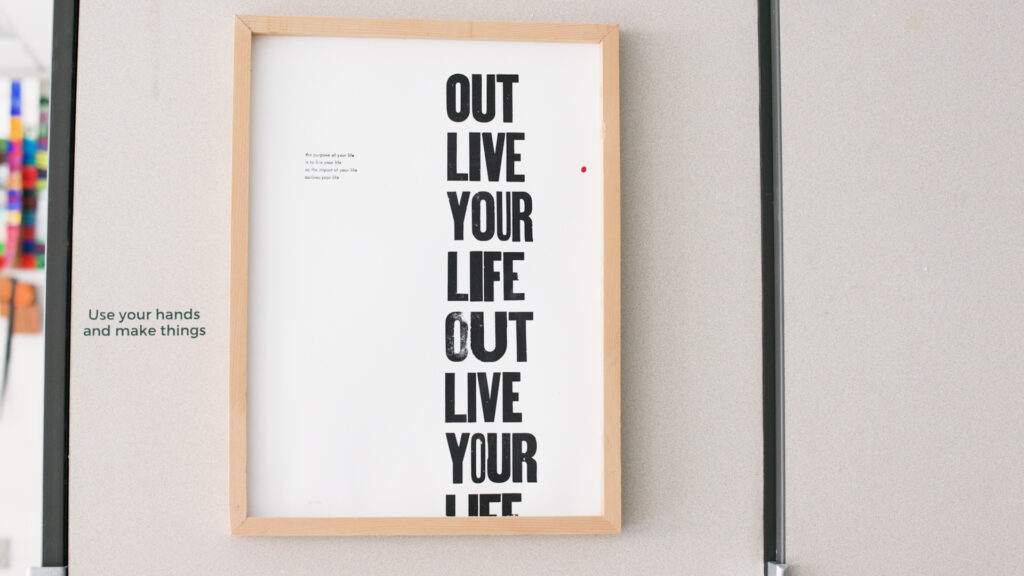

But the occasional letter, email, or unexpected gift reminds him that his work matters. He keeps a sign in the studio made by a former student who is now a graphic designer in California. It arrived in the mail three years ago, a small but lasting reminder that his influence continues in ways he cannot always see.

What satisfies him most today is not creating his own work but helping others discover their ability to create. He often tells students that almost everything they touch has been shaped by an artist, designer, or craftsperson. The bed they wake up in, the toothbrush they hold, the lighting above them, the interior of a car, the cookware in a kitchen. None of it is arbitrary. All of it is the result of decisions rooted in the principles he teaches in his studio. Even something as simple as drawing perspective cubes in high school can become foundational for a career in architecture, automotive design, industrial design, or any field where aesthetics and function intersect.

He wants them to understand that art is not a narrow discipline. It is not the stereotype of a painter in a dim room with a beret and a dangling light bulb. Artists today are designers, engineers, architects, photographers, and problem solvers. They are people who think intentionally about form, function, and experience. He works to widen this understanding from the moment students step into his classroom.

Still, he is honest with himself. If someone had told his younger self that becoming a teacher would mean giving up most of his own creative time, he might have run the other way. He acknowledges that there are days when the job feels heavy and discouraging, when certain students resist any guidance, and when he is tempted to think of all the paths he might have taken. But then he reminds himself that the job is not about reaching every student. It is about reaching some. Those who are open enough or curious enough to find meaning in the work.

His advice to himself, and to anyone starting out as an educator, is simple. Focus on the students who are willing to show up. Do not waste energy on those determined to remain unreachable. Maintain a positive attitude where possible. Show up each day. Get the job done. He holds onto the belief that for the right students, even small moments of understanding can ripple outward into their adult lives.

For Terry Szpieg, art has always offered possibility. Teaching has added complexity and challenge, but it has also given him a way to shape possibilities for others. Even on days when he feels stuck, knowing that former students are out in the world creating, designing, shaping, and finding fulfillment offers its own form of meaning. In the space between their work and his own, he finds the quiet reward that keeps him returning to the classroom year after year.

Help support Timestamp (we’re an Amazon Associate) when you buy art supplies with our affiliate links (we earn a small commission at no extra cost to you):

Shop for Acrylic Paint: https://amzn.to/43UkZLA

Shop for Canvas: https://amzn.to/4nG9q1I

Shop for Brushes: https://amzn.to/4nJQJdQ

Shop for Woodworking Tools: https://amzn.to/49XTLrc

Shop for Pottery Tools: https://amzn.to/4rRpmkX

Kara Su

Born and raised in Berlin with Kurdish roots, Kara Su grew up far from the…

Logan Sylve

For Logan Sylve, painting is a steadfast companion. “I feel like painting is my first…

Mario Picardo

Mario Picardo approaches painting as a space of personal freedom. The studio is not a…

Hill Spriggins

Originally from New Orleans, Louisiana, Hill Spriggins has been living and working in Brooklyn, New…

Brenda Zlamany

Brenda Zlamany has been painting for most of her life, and she speaks about it…

2026 Trends in Contemporary Art: What Artists, Curators & Collectors Are Talking About

Contemporary art in 2026 is evolving at an unprecedented pace. As the art world continues…